One thing that has been bugging me for a very long time is trying to identify the different Norman supercharger models. Whilst there were a number of Norman supercharger models produced, little literature remains to confirm the exact types and models. To complicate matters, there is a significant amount of rumour and guesswork that has been applied over the last half century. Various discussions refer to a wide variety of machines, including Type 70, Type 75, Type 72 and Type 45. I will present the information below based on discussion with Mike Norman, together with some (limited) literature from the era and photos of different models. My thanks to Mike for helping to pull this together.

Eldred’s Superchargers – the start of something cool.

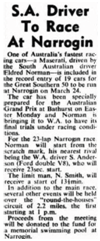

Eldred Norman became interested in manufacturing superchargers following a supercharged car being traded-in at his used car dealership in Adelaide in the very early 1960’s. Having removed the supercharger before selling the car, Eldred then sold the supercharger, and was astonished at the volume of interest expressed. This indicated a clear market, providing that the right vehicle was chosen to sell the supercharger to. Whilst there could be some benefit in selling superchargers to performance cars, there was a far greater market selling to vehicles with relatively poor performance. At this time General Motors Holden was a significant market player, but had yet to embrace the performance market… it’s first forays into factory “muscle cars”, the EH S4 and HD X2, were some time off. Holden thus became the logical target for Eldred’s manufacturing. The first Norman superchargers were made by Eldred in Adelaide, using both his own workshop and a small third-party foundry. Eldred continued manufacturing after moving to Noosa, utilizing a foundry in Maroochydore. In both South Australia and Queensland he made his own sand-casting moulds and forms.

Eldred’s superchargers were named by “Type”. Each Type was numbered according to it’s capacity in cubic inches per revolution, measured by subtracting the volume of the rotor treated as a solid form from the volume of the interior of the casing (see discussion above over how this differs from current methods of measuring capacity). Eldred made the following eight Types:

• The Type 65

• The Type 70

• The Type 45

• The Type 75

• The Type 90

• The Type 110

• The Type 265

• The Type 270

Type 65

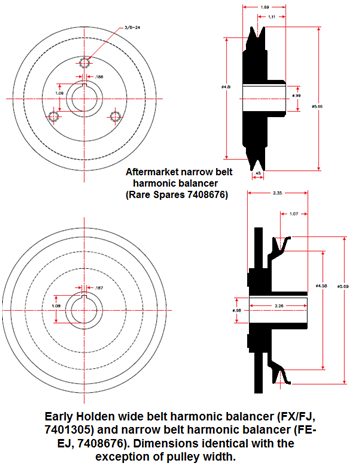

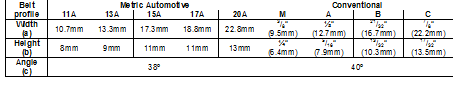

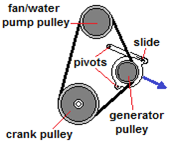

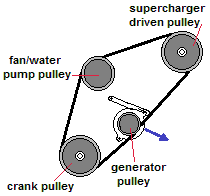

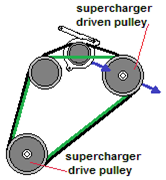

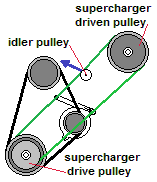

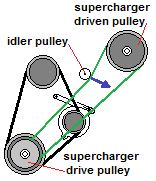

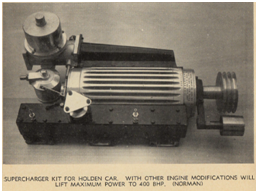

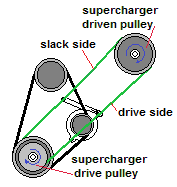

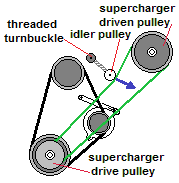

The Type 65 has a capacity of 65ci/rev (118ci/rev if measured by the modern method). It is believed that Eldred began manufacturing superchargers with the Type 65 in late 1964 or early 1965 in St Peters, Adelaide. The early Type 65’s all have cast iron casings and steel rotors, and are fully air cooled. Some of the early Type 65’s had alloy rotors though this was quickly ceased and steel used due to wear. Later Type 65’s, which were made after the introduction of the Type 70’s, have alloy casings and are water jacketed with two welsh plugs. The welsh plugs were added primarily to support the sand around the jacket void during sand casting of the housings. Type 65 casings have seventeen radial fins, cast iron liners, have Type 65 cast into the casing and have separate inlet and outlet manifolds. Both Type 65’s and Type 70’s are often fitted with Eldred’s inlet manifold, which points back towards the firewall (some are fitted with an extra elbow to point the carburetor towards the passenger bonnet spring). The early Type 65’s were mounted via the Holden grey motor generator bracket, and connected by hose to the inlet manifold. The bracket was then tensioned up to provide a tight drive belt. This line-up was changed in Noosa to the use of a steel inlet manifold made from RHS, with a separate idler pulley providing belt tension. Surviving Type 65’s that I am aware of include Gary Claypole’s alloy cased unit (which has been overhauled and photographed above), and John Brown’s steel cased unit (which I need to get photos of). The image below appears to show an early steel cased unit (judging by the colour difference between the casing and end plates) and was taken from an early advertisement for the Eddie Thomas Speed Shop in a 1965 copy of The Australian Hot Rodding Review.

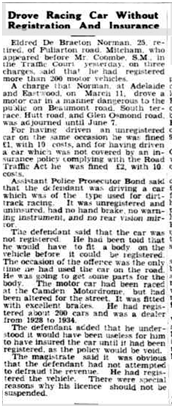

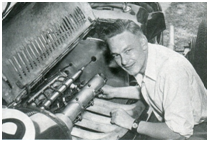

Mike Norman also drove an ex-PMG FE panelvan (repainted from red to grey) with a Type 65 supercharger around 1964-1965. Bill Norman raced a Standard 10 fitted with a Type 65 (his first race car, at age 17), which was later road-registered by Mike.

The photographs below show an early steel-cased Type 65 on an FJ Holden.

Pictured below is the steel-cased Type 65 owned by Lindsay Wilson.

Pictured below is an alloy-cased Type 65 advertised on eBay in May 2014.

Type 70

The Type 70 has a capacity of 70ci/rev (I have not had a Type 70 open to measure it’s capacity by modern methods). The Type 70 superchargers all have alloy casings (radially finned on one side, smooth on the other with a cast iron liner), alloy end plates and are water jacketed with two welsh plugs. These have Type 70 cast into the casing. Type 70’s were mounted on the passenger side of the Holden motor, with Eldred’s inlet manifold. The carburetor, usually a 2” SU, was mounted at the passenger rear of the engine bay. Externally, there is little to differentiate the Type 65 and Type 70 other than size (the Type 70 being slightly larger) and the name (Type 65 or Type 70) cast into the water jacket.

Pictured below is Lindsay Wilson’s Type 70 from his EK Holden stationwagon, with both photos showing the finned side of the casing. Carburetion is single 2” SU.

Pictured below is Peter Wooley’s Type 70 from his FJ Holden sedan, showing the smooth side of the casing. Carburetion is twin SU.

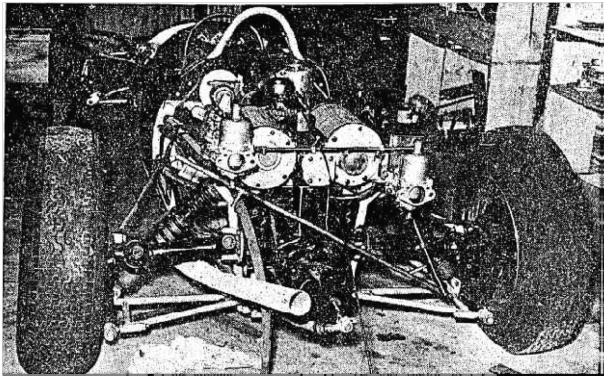

Pictured below is Ian Gear’s Type 70 from the Rowe/Wigzell SA#2 WonderCar speedcar. Carburetion is triple Stromberg 97.

Type 45, Type 75 and Type 90

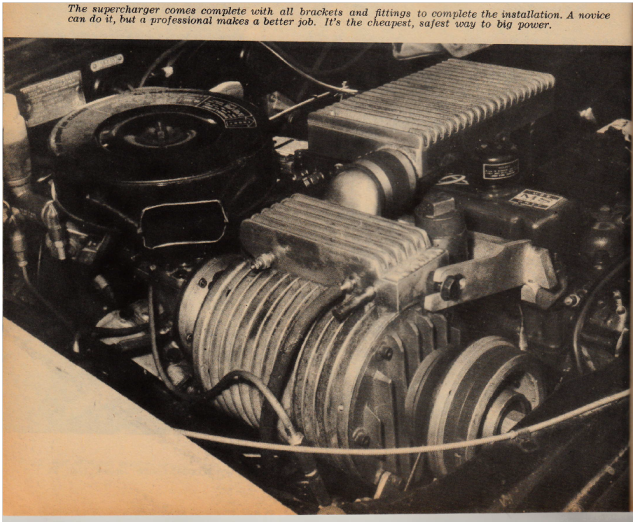

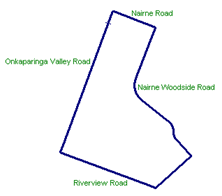

The Type 45, 75 and 90 were developed as a family of superchargers, often referred to as Series 2 (Series 1 compromising the Type 65 and Type 70). The Type 45, Type 75 and Type 90 were manufactured by Eldred whilst still living in Adelaide. Using Eldred’s measurement process, the Type 45, Type 75 and Type 90 had a capacity of 45, 75 and 90ci/rev respectively. Using the modern measurement system gives 83 and 149ci/rev respectively for the Type 45 and Type 75 (I have not been able to find a Type 90 to measure). Interestingly, when using the modern method the Type 75 (149ci/rev) has a larger capacity than the Type 110 (145ci/rev). This is due to the placement of the inlet and exhaust ports, which is not accounted for in Eldred’s method. The target market for the Type 45 was engines up to 107ci (smaller than a Holden red motor), whilst the Type 75 and Type 90 were targeted at the 186ci Holden red motor and 225ci Valiant slant-6 engine respectively. The Type 45 was sold as a blower-only package, with manifolding being made by the end-user to suit the specific application, whilst the Type 75 and 90 could be purchased as a package, utilizing the original vehicle’s carburetor. Note however that some Type 75 installations swapped Valiant Carter carburetors on to Holden 186ci engines, probably due to the 111/16” Holley 1920 or Carter BBD carburetors (235 or 260 cfm@3”Hg) being of greater capacity than the replaced Holden single barrel 15/32” Stromberg (210cfm@3”Hg), albeit less than a WW-series carburetor (280cfm@3”Hg) fitted to the HR “S” 186ci engine.

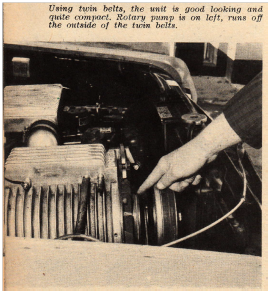

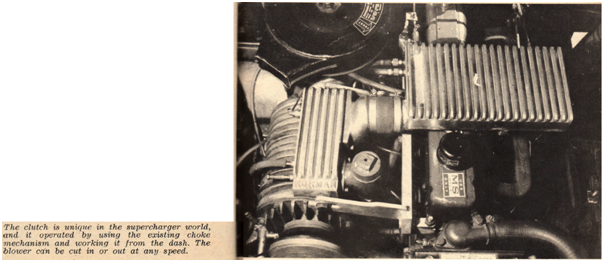

Type 45, 75 and 90 superchargers have steel rotors, radially finned alloy casings with a cast iron liner, steel end plates and integral inlet and outlet manifolds (all other Norman superchargers have separate inlet and outlet manifolds). Type 45’s have seven radial fins, whilst Type 75’s have twelve (I do not know how many fins a Type 90 had). Type 45’s and Type 75’s had “45” and “75” stamped (not cast) into the housing (I’m not sure if Type 90’s did but suspect so). The Type 45 is air cooled, whilst the Type 75 is water cooled with no welsh plugs. An article was written for Australian Hot Rod magazine in November 1966, titled Blow for Go! Norman Style. The article has a lot of technical detail, and is very likely to have been written in consultation with Eldred… giving confidence it is factual. The article refers to two models, a Standard (no clutch) and DeLuxe (clutched). The article notes three sizes:

• the size shown in the article, which is a Type 75 supercharger.

• a 4” shorter size designed for engines up to 1750cc/107ci (the Type 45 supercharger), and

• a 2¼” longer size for engines up to 4000cc/244ci (The Type 90 supercharger).

Looking at the article detail, the Standard and DeLuxe have a hard-chromed steel liner. Note that this is interesting, as Mike remembers that none of Eldred’s supercharger liners were chromed or surface treated. The majority of Eldred’s liners were made from cast iron diesel truck sleeves. At one stage, Eldred managed to secure some chilled cast iron sleeves from Repco. These were found to be too hard, and Eldred reverted back to the normal cast iron sleeves. Also of note from the article:

• steel rotors (aluminum had been tried but had only 1/8th the life of a steel rotor). The Type 75 had a rotor of 4½” diameter, bored 2”,

• cast-iron end plates (aluminium had been tried but wore the rotor ends). The Type 75 was 13/8” (inclusive of the fins). Note that this is different to the earlier Type 65’s and Type 70’s, which have aluminium end plates,

• an internal diameter of 5½” and an overall width of 12” for the Type 75,

• four ¼” vanes lots to average 2½” depth, with ½” of support at the base of the lobe slot,

• a 1½” long boss for the pulley drive key back to the front bearing on the Standard, with no boss on the Deluxe (the pulley for the Deluxe being mounted on ball races).

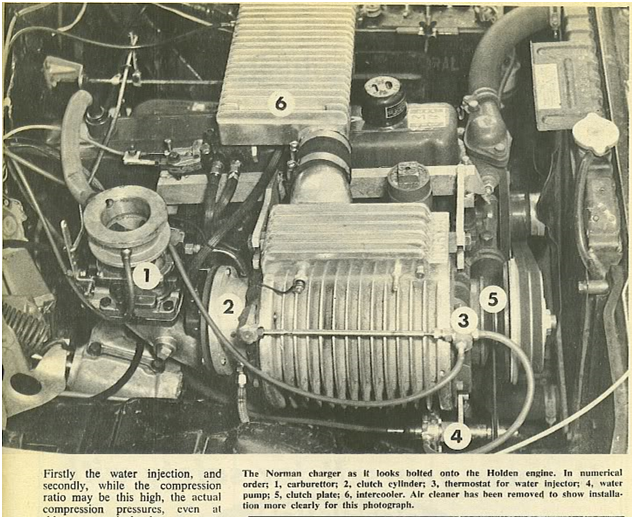

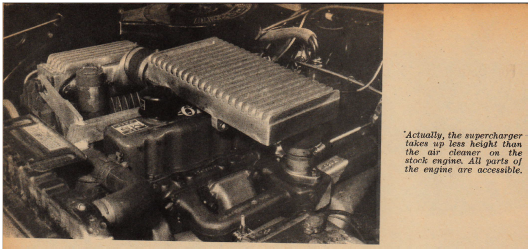

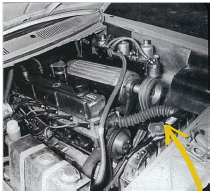

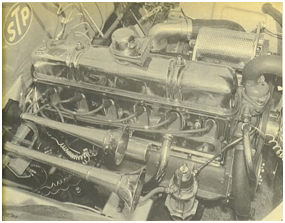

Whist the Type 65 and Type 70 superchargers were largely used on Holden grey motors (along with other engines of similar size), the Type 75 marks Eldred’s change to targeting the Holden red motor. Unlike the earlier Type 65 and Type 70’s, the Type 75 supercharger is mounted on the driver’s side of the Holden engine, with the inlet to the bottom and the carburettor on the steering box. The supercharger outlet is fed across the top of the rocker cover via a cast alloy air/air intercooler.

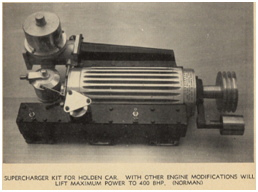

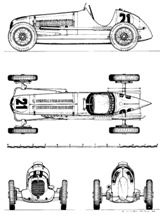

The image from the article, showing the Type 75 DeLuxe, is shown below.

An additional article was written for The Australian Hot Rodding Review of January 1967, titled Blowers for Holdens!. The article was written inclusive of a visit to Eldred’s workshop in St Peters, Adelaide (the visit must have occurred before Eldred moved to Noosa in 1966), and is again very likely to have been written in consultation with Eldred and likely to be factual. This article refers to a second series of Normans (Series 2). Images from the article are shown below.

Looking carefully at the Australian Hot Rod and Australian Hot Rodding Review images shows that they are the same vehicle, being Eldred’s HD Holden utility.

The images below show Type 75 superchargers.

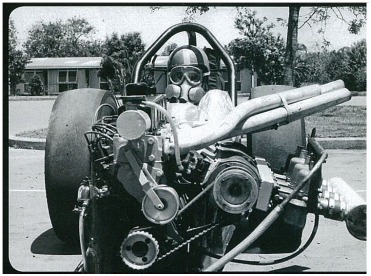

The image below shows my Type 45 Norman. As an aside, this unit has had an interesting history, having been used as a forge furnace blower in Noosa by Eldred. On request, Eldred made Super Light Weight (SLW) rotors for some superchargers (definitively some Type 110s and probably others). The Super Light Weight rotors were made from steel, initially milled from a billet, then with steel flat bar electric stick welded in place with the whole assembly then machined… no small task! The kerosene-fired forge (with the Type 45 supercharger blowing air through it) was then used to heat treat (normalize) the rotors. A Super Light Weight rotor, in an early Type 65 casing, is illustrated in Supercharge! (see image below).

Type 110

The Type 110, with a capacity of 110ci/rev (as measured by Eldred’s method) was the archetypical Holden red motor blower. The Type 110 superchargers all have alloy casings and are water jacketed with three welsh plugs. These are the only superchargers made by Eldred with longitudinal (not radial) fins. Between manufacturing the Type 45, 75 and 90 superchargers, Eldred had moved to Noosa in 1966. Production of the Type 110 supercharger may have commenced as early as 1967, though was definitely in full swing by October of 1968. The Type 110 was targeted at the Holden red motor, though saw use in some unusual places. For example, in Supercharge! (October 1969), Eldred refers to a Type 110 supercharger:

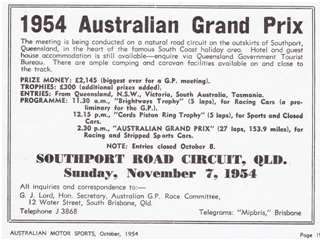

“In 1954, driving a supercharged Triumph TR2, I finished 4th in the Australian Grand Prix. On this car I used a “boost’ of 12lbs. The supercharger was a G.M. 271 Roots type unit operating at 1.1 times engine speed and driven by four ‘A’ section V belts. By the end of the race belt-slips had caused a fall in boost to a maximum of 8 lbs. Naturally I had to ‘nurse’ the belts by not using full throttle at this stage. My present Holden is some 50% greater in capacity than was the Triumph. I am using a 10 lb. supercharge from my type 110 vane type supercharger and drive it with only two ‘A’ section belts. Under these conditions the vane type is putting out almost 40% more air/fuel than did the Roots with twice the number of belts. Certainly the car is not being raced which is an enormous difference. But my belts last at least 5000 miles of normal road use. Detractors of the vane type supercharger have usually only seen the wrong unit on the job.”

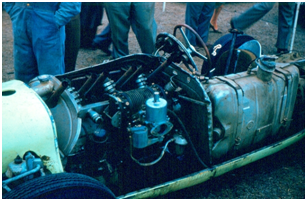

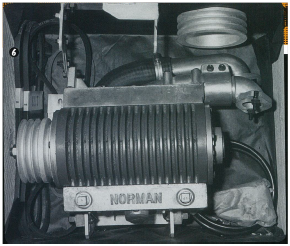

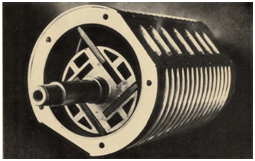

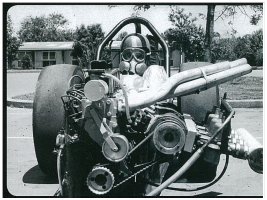

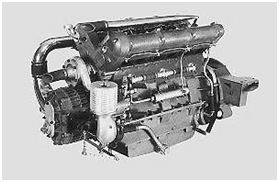

The Type 110 is also illustrated in Supercharge! (see image below). The longitudinal fins are clearly visible from this angle.

A Type 110 supercharger was also used on the Dennis Syrmis/Richards Time Machine FJ Holden drag vehicle shown below. Syrmis is renowned for being the second National Director of ANDRA, helping found Willowbank Raceway and for initiating the "Wild Bunch" and "Top Doorslammer" drawcards.

The image below (from Street Machine magazine) shows a Type 110 on George and John Cole’s Vauxhall Viva gasser.

The image below shows the Type 110 on Ken Stephenson’s Front Engined Dragster. The three welsh plugs are clearly visible from this angle.

The image below shows my Type 110. This machine has had a hard, hard life, and was last in service on a Toyota engine at 20psi. Along with being helicoiled, the casing has had the original three-welsh plug jacket removed and the polished water jacket seen in the image fitted.

Type 265 and Type 270

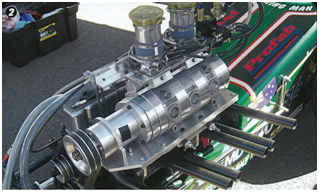

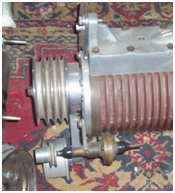

The Type 265. This is where Eldred’s numbering system becomes interesting the Type 265 supercharger does not have a capacity of 265ci/rev. Rather, it has a capacity of 2 x 65 = 130ci/rev. The Type 265 superchargers were built by joining two Type 65 superchargers end-to-end with a common rotor (and hence the naming convention – two x Type 65). The casings were joined by recessing the Type 65 units to suit studs and nuts and bolting them together before line boring and honing. The Type 265’s were built as a response to a need in the market for a supercharger to suit larger V8 engines and rail dragsters. It is likely that all Type 265’s were alloy cased and water jacketed, though potentially some were made with air cooled steel casings. Type 265’s were made by Eldred in Noosa from 1967 onwards.

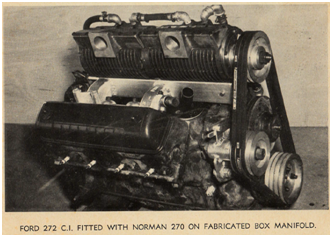

Similarly to the Type 265, the Type 270 has a capacity of 2 x 70 = 140ci/rev, and is made by joining two Type 70 casings with a common rotor. All Type 270’s had an alloy casing and water jackets, with cast iron finned end-plates. The Type 270 is illustrated on a &*#@ Y-block V8 in Supercharge! (see image below).

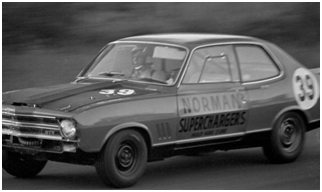

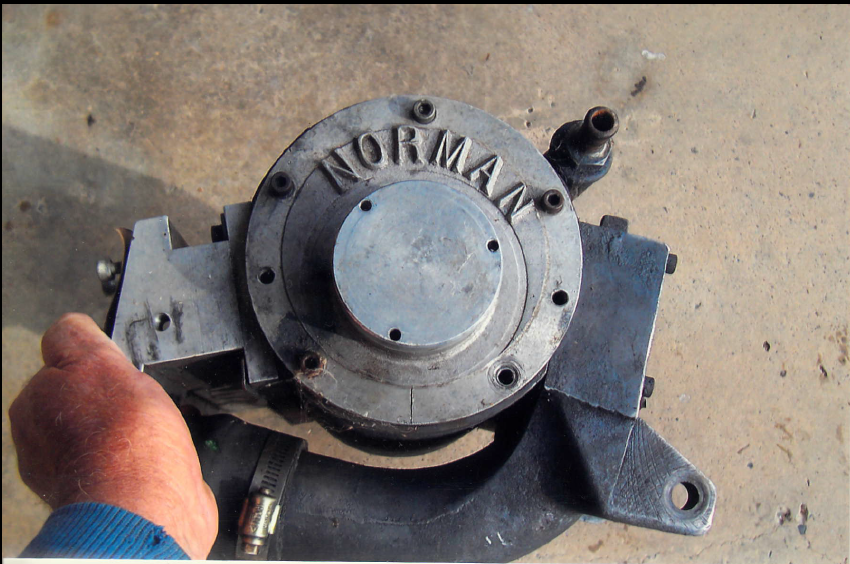

I know of only one Type 270 to have survived, which is currently owned by Mike Norman. This Type 270 was built by Eldred for Bill Norman in 1969/1970. Whilst Bill was driving a Type 110 supercharged GTR Torana, it still was not quick enough. Eldred’s answer was to build a Hillman Imp with a Buick Fireball aluminum 215ci V8, complete with the Type 270 supercharger. Sadly, whilst the Hillman was test driven for a yew yards, it was not completed prior to Eldred becoming ill and passing away.

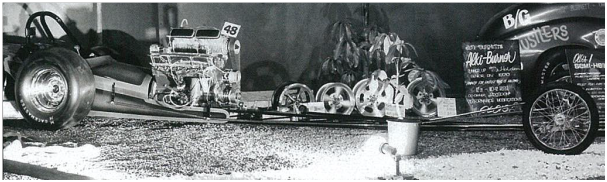

Type 265 (water cooled) and Type 270 superchargers can be quite difficult to differentiate. The main visual two differences between them are that the Type 270 is slightly larger, and all had cast iron finned end plates (the Type 265 may have had either cast or alloy end plates). The photographs below show superchargers which could be either the Type 265 or 270.

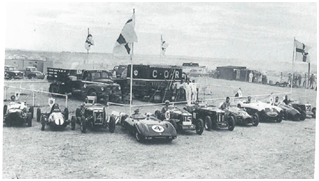

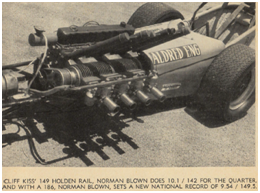

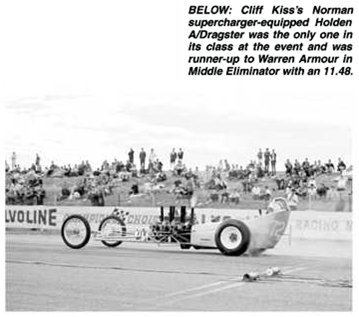

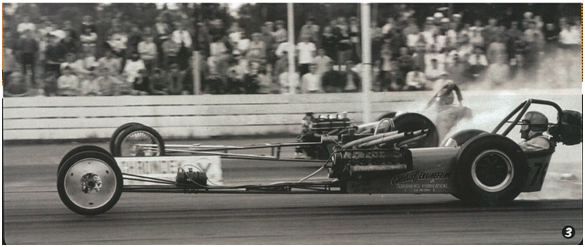

Shown below is Cliff Kiss’ front-engined dragster, taken from Supercharge! Note that Aldred Engineering is not the company of the same name currently operating out of Helensburgh NSW.

Kiss’ dragster is also shown below from Australian Drag Racing Nationals Souvenir Edition 1973:

… in this photo below from The Elapsed Times of June 2008, which shows Kiss’ dragster at the 1968 Winternationals on June 23rd 1968 at Surfers Paradise International Raceway…

… and also in these two shots from the 2009 Street Machine Hot Rod Annual.

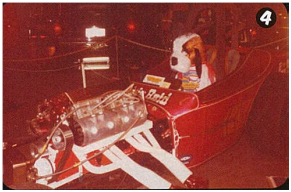

The photo below shows Chris Reid’s altered (originally built by Bill Jones and raced by Ray Knight).

Shown in the image below is the Warren Ramsay/Ian Burrows Semi Hemi front-engined dragster, running Olbis injection on a Valiant Slant-6.

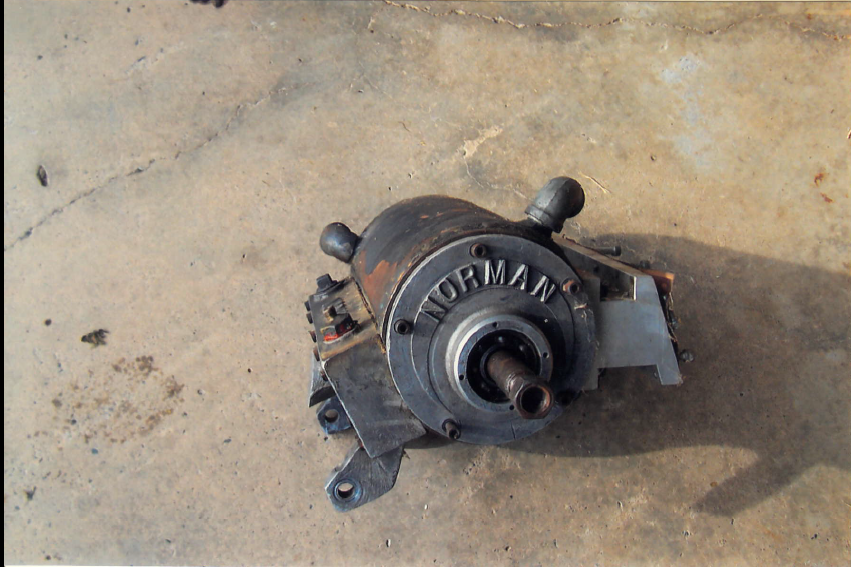

Mike’s Superchargers – the blower is back.

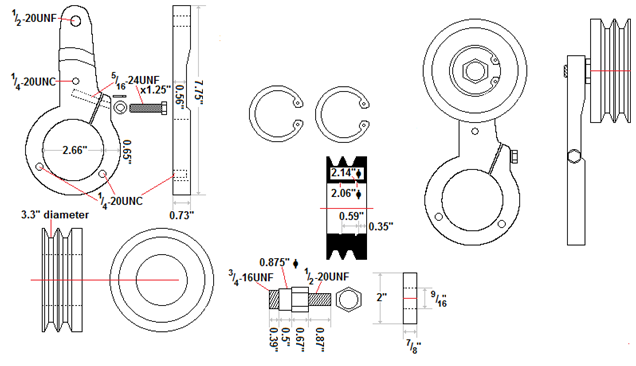

Having been raised on a diet of supercharged vehicles, Mike Norman began building some superchargers from Eldred’s design in 1973-1975. Unfortunately, the original patterns and moulds for Eldred’s superchargers, stored under the house in Noosa, had been lost. From 1978 (through to 1984) Mike ran Offroad Automatics Pty Ltd at Magowar Road in Girraween, Sydney. Whilst the business was involved in fitting automatic transmissions to Range Rovers, Mike began to tinker with superchargers around 1983.

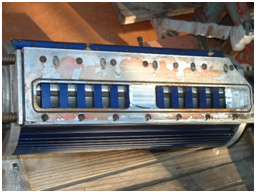

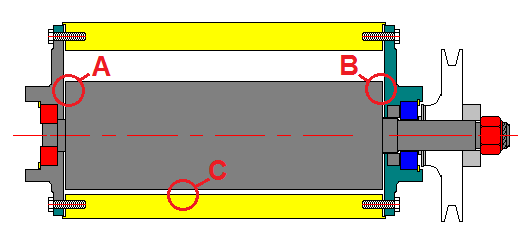

Mike’s superchargers represent a significant design change from Eldred’s. Rather than cast individual casings, Mike chose to extrude the casings from aluminium. Mike’s casings were initially manufactured by milling a 6” diameter solid aluminum billet… no easy task. Once the casing design was finalized, a two-piece extrusion was made by Comalco. The casings were then lined with a cold drawn seamless tube, manufactured in Adelaide (with a minimum order of 300m!) to a tolerance of around 0.004”. The liners were then Tufftrided in Melbourneprior to being installed. In some of the casings a rubber O-ring was fitted between the casing and the end-plates. The end-plates, of aluminium construction, were cast by Newcastle Foundries.

Mike’s rotors were milled from 4” aluminum round stock. Whist he considered having an extrusion made (similarly to the casings) the proposals from various manufacturers at the time were expensive due to the complex die and not very accurate. The non-drive end bearing support stub (shaft) is made by turning down the main aluminum body. The steel drive end shafts were made by drilling and tapping the rotor then Loctiting the screwed shaft in place. The rotor design was also different to Eldred’s, moving from four vanes to three.

By doing this, Mike was able to achieve a very deep vane slot whilst still having sufficient “meat” in between slots close to the shaft. The deep vanes allow for a long vane movement (high capacity) whilst still retaining enough of the vane in the slot to minimize bending moment. However, having a greater proportion of the vane in a deep slot moves the vane centre of mass closer to the shaft. This in turn lower centripetal force, making Mike’s vanes harder to move outwards than Eldred’s. Whilst the problem of the vanes sticking in is reduced at higher rpm, at low rpm the issue is noticeable – the noise of vanes clatter (lifting off then re-hitting the casing walls) is evident. To address this issue (clatter and the potential for increased vane wear at low revs) Mike fitted springs to each rotor vane. The springs were fitted in pockets milled into the rotor slots, and retained in place by a nylon bush. The springs were locally made in carbon steel as alloy material was not readily available locally and would have had to have been sourced from the US. Whilst this seems strange in a modern “everything is available online” world, bear in mind that Mike was manufacturing in the early 1980’s… the World Wide Web was still the domain of university geeks. Mike experimented with a number of other options to increase the centripetal force, including lightening the vanes and fitting them with lead weights.

A change was made to the material used for supercharger vanes. Eldred’s vanes are a dark brown colour, and are made from canvas backed Bakelite with a phenolic resin binder. Mike’s vanes were changed to a more modern epoxy resin based binder over a fine fabric matrix, supplied by a firm in Sydney. The cream coloured epoxy based material was much stronger and wear resistant than Eldred’s Bakelite vanes. I suspect Mike’s material was either National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) FR-4 or FR-5 fire retardant glass-cloth reinforced epoxy laminate, but am not certain. Additionally, Mike’s supercharger vanes have grooves that are milled all the way across the face of the vane. The grooves are used to assist the vanes in being able to move in and out of the rotor. The vanes should be a “flop” fit, though may experience some changes in dimensions due to moisture, fuel properties or dirt. If the vanes become a tight fit, the oily environment they operate in may allow them to form a seal with the rotor. In this case, the vanes will draw a vacuum at the vane root as they try to slide out, or will build pressure at the vane root as they slide back in. The slots allow the vane root to equalize pressure, allowing the vanes to slide freely. The slots also allow some flow of air/fuel/oil around the vane, helping lubrication. Vane grooves were not machined in the vanes made by Eldred.

Similarly to Eldred’s superchargers, Mikes superchargers employed a roller bearing at the non-drive end and a ball bearing (sometimes two) at the drive end. Some of the longer shaft superchargers were fitted with greasable drive-end bearings, though most of the bearings were of the sealed type. The bearings chosen by Mike were metric, being cheaper at that time than the imperial bearings available.

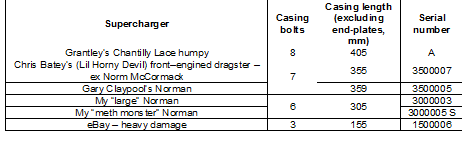

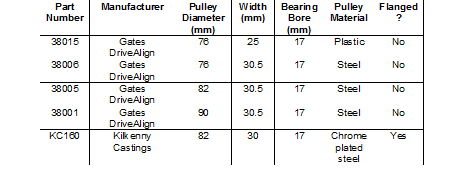

Mike made a total of six supercharger sizes (150mm, 200mm, 250mm, 300mm, 350mm and 400mm), designated by the effective casing length. The target market was engines from 500cc to 4000cc (30ci to 244ci). Whereas Eldred’s superchargers were referred to as “Types”, Mikes were referred to purely by number (for example “my Holden motor is fitted with a 300 supercharger, and goes like the clappers”). When the casings are measured, they are typically 5mm longer than the above sizes, as the end plates are recessed 2.5mm each end. The casing length is also reflected in the serial numbers stamped into the casings: the first three digits of the serial number reflects (approximately) the casing length in millimeters. Examples of serial numbers are shown in the table below.

The superchargers were identical internally, with capacity being determined by cutting the casing extrusions and milling the rotors longer or shorter. Both short and long drive shaft lengths were supplied, with the 300, 350 and 400 superchargers typically fitted with longer shafts whilst the 150, 200 and 250 superchargers typically fitted with shorter shafts.

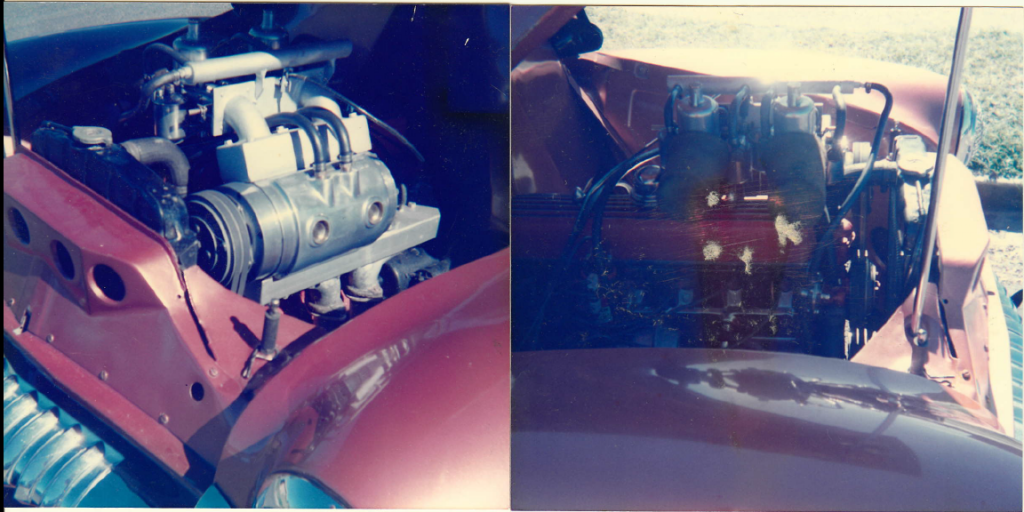

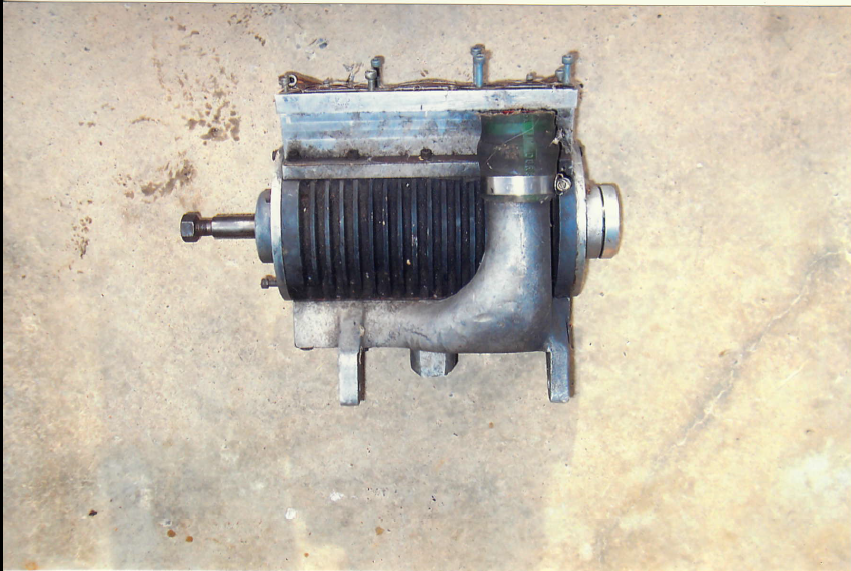

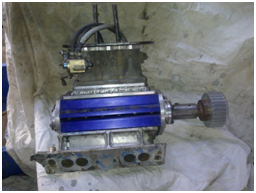

The photographs below show a 150 supercharger.

The photograph below shows a 300 supercharger.

The photographs below show a 350 supercharger. As an aside, this supercharger has an interesting history, having spent time on Mike Normans’ 122ci SOHC Triumph Dolomite Sprint.

The photographs below show a 400 supercharger.

Around 1984 Mike was commissioned to supercharge the new four-door Range Rover owned by the managing director of Leyland Australia. This vehicle originally had 9.5:1 compression, and required new low compression pistons to go with the supercharger, manifolds and water injection. All up the project cost around $3500. Mike ceased automatic transmission operations in Girraween in 1985, moving to Noosa. The advent of newer more efficient supercharger type such as the Whipple and Eaton superchargers made for a declining market, and supercharger production was ceased.

Cheers,

Harv (deputy apprentice Norman supercharger fiddler).

[/URL

[/URL

[/URL

[/URL